Operation Ursula

by Julio de la Vega

The involvement of Italian submarines in the Spanish Civil War is well known. They are often considered to be the only foreign subs that engaged in combat operations during that war. Many other warships from Great Britain, France, Italy and Germany were part of the surveillance operations agreed to by these countries for the purpose of guaranteeing the neutrality of foreign powers and enforcing the arms embargo. Of these, the only war action recorded was a retaliation bombardment in April 1937 of the port of Almería by the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer after her sister ship Deutschland suffered an aerial attack by Republican (1) combat planes. True, their actions showed a somewhat less pure neutrality than they pretended but, even so, they did not fight directly. Historians record that Italian submarines and some surface units under the Italian flag were exceptions and that they actively participated all throughout the war. Although officially denied by the Italian government, their combat operations were not a secret to anyone at the time.

But the so called sottomarini legionari ("legionnaire submarines") were not the only foreign submarines that engaged in combat operations. There was another similar involvement in a much more downsized, short, secretive, and ultimately unsuccessful operation. Its codename was Operation Ursula, and it was undertaken by the German U-boats U-33 and U-34. The mission was not to be unveiled until after the end of the Second World War when the French naval officer Claude Houan, inspecting Kriegsmarine archive papers, found the ones concerning Operation Ursula. There was enough proof in those documents to ascertain that the responsibility for the mysterious sinking of the Republican submarine C-3 belonged to U-34. Were it not for this sinking, the German mission, that lasted only a single month at the end of 1936, would probably have remained unnoticed and perhaps lost to posterity. In this article both the mission and the sinking will be described to the degree that the available sources allow us to do so.

Naval strategic situation at the beginning of the war

The official date for the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War was July 18th, 1936, though the army units in Spanish Morocco had staged an uprising a day before. Intended as a military coup, it failed in the major cities of Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia, and only succeeded in some less important cities and large areas of rural Northern Spain. In military terms, it meant that the only hope for the Nationals to change the balance in their favor was the so called "African Army", the troops garrisoned in Spanish Morocco. Under the orders of General Franco, it numbered only some 30,000 soldiers, but was by far the best trained, commanded and the most efficient force in Spain at the time. Its units were the ones that carried out the fall offensive that brought the frontline to the outskirts of Madrid and placed the southern and northern territories into the hands of the Nationals, thus making available to the forces in the north much needed war supplies and providing them with a grip on a contiguous territory.

In the beginning there was a crucial problem for Franco. He needed to shuttle his troops to mainland Spain. For that, he needed some territory in the far south of the Spanish peninsula, and he had to cross a sea inlet, the Straits of Gibraltar. The first issue was sorted out by the bold action of General Queipo de Llano, who, in spite of the fact that he had no territorial command and had very few troops at his disposal in those early days of the war, seized the city of Sevilla against all odds; connected up swiftly with the town of Cadiz home of a naval base (already in the hands of the National forces); and quickly enlarged the territory under his control.

But the main problem remained unresolved since the bulk of the Spanish naval forces were in Republican hands and its obvious principal mission was to prevent any troop traffic from the African colony to the mainland. The balance of naval forces was clearly discouraging for Franco: although both sides had a battleship (sister ships, both ordered in 1914 and not modernized since with a subsequent limited operational capacity), the Republicans had three light cruisers for one the Nationals and the difference in destroyers was appalling: eleven Republican (nine modern and two old) for a single (old) destroyer on the National side. In minor units, submarines apart, the situation was a little more even. But in submarines there was really no balance at all: the twelve submarines in service of the Spanish navy were all on the Republican side - a fact that among other things meant that no submarine attack could be attributed to Franco's naval force.

Nevertheless, there were some other circumstances that alleviated the desperate naval situation of the Nationals. The first was the seizure from the beginning of two of the three Spanish naval bases: El Ferrol and Cádiz. In the first, located in the Northwestern corner of the Spanish peninsula, two heavy cruisers, Canarias and Baleares (actually, a modernized version of the British Kent class), had been built, and at the outbreak of hostilities both were near completion. The other base, Cádiz, was in the Strait (Strait of Gibraltar) zone. So its possession denied direct control of the Strait to the Republicans and gave control of both sides to their enemies who in the absence of naval units could always protect the short distance between Cádiz and Ceuta from the air. Air attacks against ships were not very accurate at the time but they had a remarkable dissuasive effect, most of all when directed at an isolated target. This left Cartagena, in the middle of the Spanish Mediterranean coast, as the only base for the Republicans. This situation gave rise to the conclusion that the obvious choice for submarine attacks aimed at easing Franco's position was to attack around Cartagena and along the route Cartagena-Gibraltar. That was exactly what the U-boats did.

Even more important was that the state of its crews was a major setback for the Republican fleet. Republican naval officers were believed to be the most politically conservative in the Spanish armed forces, thus they were inclined to embrace the rebels' cause. Partly because of this, clandestine committees of sailors had been created in almost all units, modeled after the ones the Soviets set up years before in the Russian navy. When the war broke out they had already displaced the commanders and all of the officers whose allegiance was uncertain (who were arrested if not directly shot) and taken over control of the ships. The government tried to establish control by appointing new commanders and officers (these were in short supply) however the appointees were usually inexperienced junior officers or plainly incompetent men appointed only for their political views. Anyway, the commanding officers were controlled by the shadowy committees which were always ready to denounce them as disaffected if they did not give in to their desires. The result was a mix of incompetence, lack of discipline, abandonment of duties and drills, and in quite a few cases of more or less disguised cowardice. Needless to say, all this anarchy greatly diminished the effectiveness of the Republican Fleet in contrast with their much smaller but disciplined, spirited and well commanded opponent. In submarines in particular (which demanded a highly skilled, trained and cohesive crew), these shortcomings on the Republican side had clearly negative consequences and C-3 was no exception to the rule.

Naval situation in the autumn of 1936

At the very start of the war, orders were issued by the Ministry (2) sending the fleet to the Straits of Gibraltar to initiate a blockade. Franco could only transfer two light infantry battalions by sea to Cádiz before it was effective. The reaction was to gather every available means to shuttle the soldiers to the peninsula by air. It worked well considering the scarcity of aircraft. But, even so, the fact remained that only the men and their personal weapons could be transported that way while their equipment had to be shipped separately and was left behind. So, against odds and against some counseling, Franco decided to take a risk and in an "all or nothing" move, organized a small convoy to cross the Straits. This turned out to be successful and broke the blockade on the night of August 5th. The Republican fleet reacted furiously the next day and their cruisers and destroyers bombarded the ports on both sides, sinking a National gunship in the Bay of Algeciras (it was later refloated, and was in service again by February 1937). For the rest, it did not inflict very much damage, but in any case the blockade was stiffened by using the port of Málaga as an advanced base, and no other attempt to break it could be made. That was the situation when the idea of sending German U-boats to Spanish waters in covert operations was first conceived. Its main defender was Admiral Canaris, but he gained little support at HQ and higher spheres, and the plan was not accepted. Not yet. But, "just in case", a few preparations were made.

Later developments however, favored the Nationals. On September 21st, a Republican fleet comprised of a battleship, two cruisers and six destroyers was dispatched to the northern waters in the Bay of Biscay area to regain control of the sea and support land operations. Previously, an especially equipped Potez 54 bomber was sent to El Ferrol to sink or disable the brand new heavy cruiser Canarias hurriedly completed and just ready for action. The aircraft reported success but although they almost prevented the cruiser from sailing, the damages were slight. The Republicans left a force comprised of a light cruiser and five modern destroyers which they considered sufficient to maintain the blockade of the Straits of Gibraltar. But, once the ships sent north bypassed the Spanish northwest corner, the Canarias along with the other cruiser in National hands, the Almirante Cervera, set sail and rushed to the south, arriving there on the 29th. They spotted two destroyers on patrol, Almirante Ferrándiz and Gravina. The cruisers sank the first (3) and forced the second to take refuge in Casablanca (French Morocco). Remaining in the area, they paved the way for the convoys to resume. Amazingly when the Republican warships detached to the north returned by mid-October they crossed the Gibraltar Straits without attacking the National cruisers based in Ceuta. They never went back to the Straits; thereafter, the route Ceuta-Cádiz was cleared for Franco´s forces.

So that's how things were at the beginning of November when Operation Ursula was launched. Overall, the Nationalists had dramatically improved their naval situation and strengthened their forces. But their enemy, concentrated mainly between Cartagena and Málaga, kept their fleet virtually intact. If as time passed it could enforce discipline and train its crews adequately as the army had done where forces in disarray were slowly giving way to a more organized fighting force, it would pose a severe threat to Franco's Navy with its inferior numbers.

Operation Ursula: the mission

One of the first things both belligerents did from the start was to hurriedly seek help from their potential allies. These were France, Britain and the USSR for the Republicans, and Italy and Germany for the Nationals. In Berlin, at first, the Spanish emissaries were received rather coldly. The Reich, of course, sympathized with Franco's cause, but the prevailing thought was that he would not be able to win the war. However, soon two factors altered its position. The first was the strong Russian support given to the Republic which caused great concern about a possible future communist Spain. The second, and probably the most decisive, was the enthusiastic support given to the Nationals by the Italians who immediately began to deliver the equipment Franco most needed, particularly transport aircraft. Germany then followed suit, sending material and soon after also military personnel. But these army, air force and navy men, were sent only as instructors. They were not to be involved in combat operations and although later they acted as frontline troops to some extent, it was not so at the beginning.

During the first weeks of conflict very few voices suggested a more direct participation, Admiral Canaris being the most relevant of them. A change of mind occurred again, when the Italians informed Germany that they would send submarines to help Franco with direct action. In October they had begun their patrols. It would imply a breach of the declared neutrality and though submarines are difficult to identify and easy to conceal, their attacks in the Mediterranean Sea would deceive no one since everybody knew that all Spanish submarines were on the Republican side. But Mussolini, who of course would deny any participation by his country in those actions, seemed not to care very much. That caused the hesitating Germans to act themselves. The Italians were essential for that course of events in two more ways. First, they ensured the covertness of the operation since the German attacks could easily be charged to the not-so-secretive Italians. And second, they were also the reason for the operation in another, not so obvious sense. Germany was eager to show the Italians that the Reich had regained military muscle, particularly in submarine warfare. This can be proven by the fact that Italy was informed from the start of the U-boat operation while Spain was not informed until the development of the operation made it unavoidable.

It was decided to intervene in a way that was quite different from the Italian action. To begin with it had to be an operation of less magnitude. In 1936 Germany had few U-boats capable and ready to be dispatched to the Mediterranean Sea. So, with the idea of a sustained operation that required only a few of the boats the number of units was reduced to just two. And more importantly, it had to be a really furtive action, being that covertness was the main priority of the mission. This feature had great relevance in the planning and execution of the mission. With these criteria, orders were passed down the chain of command to the headquarters of the submarine force (FdU, later to become BdU) with Käpitan zur See Dönitz as its chief. There, someone had the idea of giving the operation the codename of "Operation Ursula", after Dönitz's daughter. The careful planning of the operation began under the supervision of Konteradmiral Hermann Boehme, Flottenchef (Fleet Commander).

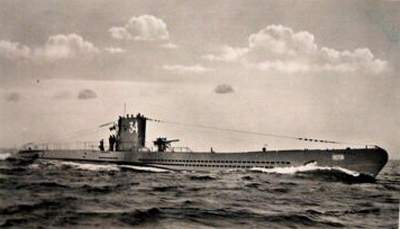

The first task was to select the boats. They had to be oceangoing boats (as opposed to the smaller Type II coastal boats). The class selected to perform this mission was the new type VII class (type VIIA), which were currently available only in the 2nd Flotilla (Saltzwedel), under the command of Fregattenkapitän Werner Scheer. The flotilla was not yet complete: of the planned ten boats (U-27 to U-36), only five were commissioned by October 1936, the last of them (U-30) being ready for service that very same month. This one being discarded, there remained just four boats (U-27, U-28, U-33 and U-34) available for the first tour. Taking into account that the whole flotilla was scheduled for commission before the year ended, up to three boats could be sent at a time to the Mediterranean. But a more conservative approach suggested that this figure be reduced to just two allowing a margin for mechanical failures, delays (actually, the commissioning of U-32 did not happen until April 1937) and other possible problems. This was accepted, and finally U-33 and U-34 were selected to launch the operation. For this operation they were assigned the codenames Triton and Poseidon respectively.

The next issue was that of the crews or to be more precise, that of the commanders. The crews with the exception of the commanders and the first watch officers already assigned to each boat were kept and each man had to swear to keep the operation absolutely secret for the rest of their lives under the penalty of death. Not that there was anything wrong with the present officers, they just didn't have much experience, but for both Ottoheinrich Junker and Ernst Sobe, (in command of U-33 and U-34 respectively) it was their first U-boat command and they had just commissioned their submarines in August and September of that year. It was felt that more experienced officers were needed and temporary replacements were sought.

Kapitänleutnant Kurt Freiwald was selected to command U-33. He had been in the submarine arm from the beginning and as early as July 1935 had commissioned U-7 and was still her commander in the fall of 1936. Prior to that he had been a torpedo specialist. He was a very well thought of officer in the Kriegsmarine however, there may have been an additional reason for his appointment. He had been the youngest officer in the Court of Honor that judged Reinhardt Heydich's misbehavior in 1931 resulting in Heydich's expulsion from the navy. A good action record might help protect Freiwald from any future attempts at revenge from such a powerful enemy.

The German U-boat U-34

The commander chosen for U-34, a submarine that was to have a shorter life than U-33, was an even more experienced officer, Kapitänleutnant Harald Grosse. Although he had commissioned his own boat U-8 a month later than did Freiwald, he had lived through the pre-history of the renewed German submarine arm, and indeed that of the Type VII itself. In the late twenties, the Dutch Company, IvS (Ingenieurskaantor von Scheepsbouw), designed a submarine based on the Great War type UB III. IvS was actually created by the German shipbuilders Vulkan, Germaniawerft and Weser and financed by the German government in order to circumvent the Treaty of Versailles' restrictions against Germany building submarines.

The boat, with a displacement of 745 tons surfaced and 965 tons submerged, a length of 72.38 meters, and a top speed of 17.0 knots surfaced, was assembled as a private venture in Cádiz by the Spanish shipbuilders Echevarrieta y Larrinaga with sections brought in from Holland, and launched in October 1930. The boat was named E-1 meaning that it was built for Spain (the "E" class was to follow the "C" class already in service and the "D" class already under construction but never completed). In 1931, sea trials took place in Spanish Mediterranean waters and were conducted by German officers. Later, when the Spanish navy declined to buy it, a customer was found in Turkey. The same team, with Turkish officers (4), brought the sub to Turkey in 1934 where it received the name of Gür and remained in service until 1947. E-1 was a predecessor of the VII class, and the young Harald Grosse had been one of the officers manning the boat. Besides his experience and familiarity with the type, Gosse had been operating in the same waters U-34 was to patrol.

The Turkish submarine Gür

It was also decided that both commanding officers would bring with them their watch officers from U-7 and U-8 because of their prior experience working together.

A zone of operations was assigned to each boat according to an imaginary line along 0.44 degrees W in the Mediterranean. For U-33, that meant an area from Cape Nao to Cape Palos. The operational area for U-34 was to be from Cape Palos westwards. Cartagena, the main Republican naval base, was in the sector assigned to U-34 while U-33 covered more open ocean although the port of Alicante was in her sector.

The instructions stressed secretiveness and security over any other consideration. The Spanish Nationalists were not to know about the operations although the Italians did for reasons of coordination. The boats would be submerged all day and surface only at night to recharge batteries and transmit to Germany. There, they depended only on Admiral Boehme to whose staff they were linked by complicated radio codes. In case they had to surface by day and were observed, the U-boats had to show the Royal Navy White Ensign. And, if the need arouse to put in to a port due to mechanical failure or any other reason, they had to enter the Italian naval base of La Maddelena (Sardinia) under the Italian flag and wearing Italian uniforms. And, last but not least, the submarines could only attack Spanish Republican warships after positive identification which practically forbid night attacks.

Operation Ursula: the execution

On the night of 20-21 November 1936, U-33 and U-34 left Wilhelmshaven to perform a previously announced "Training Exercise Ursula". Two days before, the German Reich had officially recognized Franco's regime. But the chosen date had more to do with the calculations made to cross the Straits of Gibraltar on a dark moonless night. Once on the high seas their crews stripped the boats of any visible markings. They crossed the Straits on schedule, navigating surfaced together during the night of 27-28. Even though they were already in the Mediterranean they had to wait until November 30th to start patrolling their assigned areas to allow Italian submarines to leave them as it had been agreed. Until that date, sub-to-sub attacks were strictly forbidden.

On the planned date the two boats separated and began patrolling their respective areas. At least in theory they could not count on the element of surprise though. Other boats had been there before. On the 22nd, the Italian submarine Torricelli had slipped quietly into the area where the Republican fleet was anchored off Cartagena, and chosen a target at will. The Republican navy had not adopted any antisubmarine measures (only anti-air measures) because there were no Nationalist subs to defend against.

The victim selected was the Miguel de Cervantes, a light cruiser belonging to the modernized Emerald class built for Spain. The two torpedoes fired hit the cruiser amidships. Thanks to the proximity of the base, the ship could be towed to port and did not sink. But she was severely damaged and was out of service for most of the war. The enemy then was alerted, which was bad news for the Germans. Better news was that the salvage operation allowed them to identify some torpedo fragments thought to be of Italian manufacture. Therefore, the press outrage against "foreign submarines" soon pointed to the Italians, and any further attacks would surely be blamed on them unless positive identification suggested otherwise.

But it was neither the precautions taken by the Republicans nor the lack of targets that would ultimately put the mission in jeopardy. Grosse was the first to attack the very same evening of the first of December. He fired a torpedo at a destroyer but missed and hit a shoreline rock. Amazingly, no one seemed to investigate the mysterious explosion. On the 5th, again a single torpedo fired at a destroyer missed (this time the target's name was identified: it was the Almirante Antequera), this time without an explosion. On the 8th, another attack against a similar target resulted in the same outcome. Things were not going better for U-33. For Freiwald, however, the problem was not torpedo malfunction, but the difficulty of gaining a favorable firing position against very fast targets (the Spanish Sánchez Barcáiztegui class of destroyers could make up to 38 knots).

Other times the limitations imposed on the mission forbid the attacks. On one occasion, the proximity of a British destroyer caused Grosse to abort the attack. It was more painful for Freiwald. On the night of December 5th, the Republican cruiser Méndez Núñez passed in front of him with a screen of destroyers. The view was the dream of any submariner but it was dark and the instructions about absolute positive identification were clear so he had to let them pass.

Every incident was duly reported to Berlin by the U-boats. There, the results, or more accurately the lack of results, reinforced the views of those who were against the operation. More people began to think that this mission offered very little to win and much more to lose. Besides that, headquarters got word that the German naval attaché sent to Spain, Korvettenkäptain Meyer-Döhner, had warned Capitán (later Admiral) Moreno, Commander of the National Fleet, of the presence of German forces in the area of operation, making everyone nervous about a possible security breach. Finally, it was the Minister of Defense, Von Blomberg, who decided to cancel Operation Ursula on December 10th and issue orders to the U-boats to withdraw next day and return to Germany. The Italians would take over the patrols from the 12th onwards; no more Saltzwedel U-boats would be sent to the area.

Both boats then took a return course along the Spanish southwestern coast. At 14:00 hrs, U-34 was sailing submerged off Málaga when, looking through the periscope, Grosse saw the clear outline of a submarine surfaced and sailing at 11 knots four miles SW of the lighthouse and heading to the port. Perhaps in other circumstances his strict instructions would have prevented an attack, because a torpedo explosion could be easily seen from shore, there were several boats in the surrounding area and, after all, the mission had been called off. Moreover, the attack position U-34 could reach was not a very good one. But inside the boat there was a sense of frustration and the anxiety over the chance to crack down on a prey was just too much to resist. After recognition, Grosse decided to attack. Visual observation identified the boat as a Spanish submarine of type "C". It was "C-3".

The submarine C-3

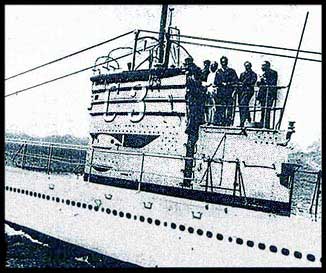

In 1931, Spain had twelve submarines in active service. They were grouped in two flotillas, one of "B" class boats and the other of "C" types, numbering six units each. Their identification was that of the type with the number from one to six. All were of Dutch design with the "C" type being larger and more recent.

Type "C" submarines were designed by the Dutch company Holland Boat, and built under license by the Sociedad Española de Construcciones Navales in Cartagena. The six units were commissioned between 1928 and 1930. Their length was 73.3 meters with a displacement of 925 tons surfaced and 1,144 tons submerged. Armament consisted of six torpedo tubes, four in the bow and two aft, and a single 75 mm. gun on the deck. They were capable of 16.5 knots with diesel engines on the surface, and 8.5 knots submerged. Maximum depth was 90 meters. Forty men, four officers and thirty six ratings, made up her crew. The Spanish Navy was quite satisfied with the boats' performance, all of them sailing without major trouble until the war broke out.

The Conning Tower of C-3

When the war started, all the boats suffered the crew's upheaval that immediately turned to open revolt, deposing the officers. In contrast with other naval units, however, the handover was bloodless in the submarine force. The Government tried to impose order on this mess and appointed commanders from among the few officers considered trustworthy, or at least those not suspected of having a friendly attitude towards the enemy (5). Even these often turned out to sympathize with the Nationals and frequently spoiled operations or defected and changed sides when they saw an opportunity. To add to this problem, the commanders were overseen by the revolutionary committee of each ship that held the real authority. The result of all this was a lot of inefficiency, clumsiness and the leisurely fulfillment of duties, drills and maintenance. In 1937-38, a solution was attempted by bringing in Russian officers to command the remaining submarines still in service, and even the flotilla, but it had little effect apart from the bitter complaints of the Soviet sailors about the crews. The final outcome was that the Republican submarines did not achieve a single sinking throughout the whole war. The only victories credited for subs were the capture of some unarmed trawlers at the beginning of the war.

C-3 was no exception to the rule. At the outbreak of the war, the commander, Capitán de Corbeta Javier Salas was absent in Madrid, where he was arrested. In the boat, the I WO, Teniente de Navío Viniegra was also arrested along with one of the two junior officers, Alférez de Navío Jáudenes. The remaining junior officer, Alférez de Navío Antonio Arbona, was appointed commander, with the acquiescence of the crew. To his lack of experience in the job, it had to be added that he had been very recently transferred from another submarine of the other type in service, B-5. To give him a helping hand, a watch officer was appointed: Agustín García, previously a captain in the merchant navy. They did not seem to form a competent team, and actually they didn't.

The short operational history of C-3 can be summed up by saying that she moved around but didn't fight. The first mission was to escort a tanker to Tanger (then an international zone). Afterwards, she patrolled around the Straits of Gibraltar. In August, she was dispatched to Biscay Bay with some supplies for the isolated Republican northern zone, and the order to localize and attack National warships (she found none). Called back to the Mediterranean by the end of August, she entered Málaga on October 6th. Finally, we find her on December 12th sailing off Málaga.

The sinking

When C-3 was spotted Grosse was aware that it wouldn't be an easy job to send her to the bottom. It was not only the oblique angle giving him concern. He could see several men on deck and in the conning tower. There were more eyes around too. First, there were those on shore, only five miles away. But these were not the most important ones. Some other small ships were around more or less two miles away in several directions including a couple of trawlers working there Joven Antonio and Joven Amalia; a coastguard vessel the Xauen; and a small patrol boat that belonged to Tabacalera (6), the I-4. And the sea was calm. The crowded waters forced U-34 to raise her periscope only for very brief periods to make calculations. The torpedo had to be set to a shallow depth. And of course, there was the nervousness caused by the previous failures to hit their target and the torpedo exploding after a miss or not exploding at all. It had to be a single torpedo, a single chance.

Grosse lowered the periscope as soon as the torpedo was fired. He would listen, not watch. Tension and anxiety were high while waiting for the characteristic sound of an explosion. But no sound came. When he was already sure that again it had been a dud, and about to give orders to slip away from there, a crewman handed him the earphones of the hydrophones. Then he heard the various sounds that usually announce a sinking. But Grosse did not raise the periscope to check. Now the first priority was to leave the place unnoticed. That night, he surfaced and sent a message to Berlin: "(from) Poseidon, 1603 K: AQ 14:19 Sunk red sub type C off Malaga". The next night, a more detailed message followed saying that identification was doubtless and that after the impact the enemy submarine had disappeared.

Three crewmen from C-3 survived: the watch officer, Agustín García, and two seamen, Isidoro de la Orden and Arsenio Lidón. The former was speaking with the commander who died along with 36 crewmen. The other two were on deck aft, throwing the garbage into the sea as they had finished lunch at about two p.m. At 14:19 p.m. suddenly the submarine shuddered, flames erupted and a dense column of white smoke rose. Then her bow tilted violently, with a slight list to starboard. And with no time to react the boat sank almost instantaneously. The men from nearby boats confirmed this description: they saw the flames, the white smoke and the submarine sinking immediately and nothing more. The descriptions of the event from people ashore were worthless and contradictory.

The one common thing among all of the witnesses of the event was that nobody saw any trace of U-34. No one noticed a periscope. Some days later in his report, the watch officer García wrote that the fifth man on the bridge of C-3, Seaman Francisco Fuentes, who was on watch duty, didn't see the trail of a torpedo. But later when the surviving seamen told their tales they did not refer to any fifth man. So we may conclude that the most probable explanation was that García lied. The real facts, that he was chatting leisurely with the commander and there were only two other seamen busy throwing things overboard and no one else was on the bridge or on deck, were not very favorable for him. It seems therefore that there was nobody on watch duty when C-3 was sunk.

The first press release published by the Republicans blamed a submarine, "evidently foreign", for the loss of C-3. The official report was however made with a cooler mind. It was dated December 22nd, addressed to the Fleet Commander and signed by the Chief of the submarine arm, Capitán Remigio Verdiá. The conclusions ruled out the explosion either of a torpedo or a mine, giving five reasons for it:

- No water column like those typically produced by either torpedo or mine (60 to 80 meters high) was observed.

- There was an explosion, but not as big as that produced by one of those weapons as it should have been seen by the witnesses.

- No one on board saw a trail from a torpedo or a periscope.

- No one among the fishermen and other people around saw them.

- No fragments fell upon the survivors.

Of these arguments, the 4th was somewhat weak. The 3rd was weak too, but it did not seem so if the "fifth man" was introduced into the scene as the WO had done in his report. But the remaining three were strong enough to support another cause for the sinking. Moreover, the area was swept for mines, but none were found. All this suggested an internal explosion. The report did not think it probable that a battery explosion caused the tragedy because the batteries were not fully charged and previous explosions of this sort had not broken the hull. Neither could it have been an internal explosion of a torpedo for the same reasons mentioned above. Verdiá then concluded that either it had been an explosion in a torpedo's compressed air cylinder, or the explosion of a low power device "placed by a criminal hand". Nevertheless, the first official version was not changed for propaganda reasons.

What then did sink the submarine? Putting all the pieces together, we may well reach the conclusion that the single torpedo fired by U-34 did really impact on C-3, but without exploding. Instead, it penetrated the hull and prompted an explosion of the batteries that produced both the flames and the thick white smoke, quickly sinking the boat. This was also the conclusion of a recent survey published by the Spanish Navy magazine (even believing in the "five-man" version).

Aftermath and conclusions

The return journey of U-33 and U-34 was uneventful. On December 21st they safely arrived at Wilhlelmshaven. There the temporary commanders and watch officers handed the boats over to Junker and Sobe the previous commanders and left. Grosse was given command of a new boat U-22 (Type IIB), belonging to the newly created 3rd flotilla (Lohs). Freiwald was given U-21, of the same type and flotilla. But his was a somewhat non-typical career and he did not remain on that boat for long. Both were decorated but as the only one credited with a victory over an enemy warship, Grosse was awarded the Goldene Spanienkreuz ("Spanish Golden Cross"), the only Kriegsmarine man to receive it, while Freiwald had to be content with the much more common Spanish Cross in bronze. Anyway, to keep the secret, the awards had to wait On February 8th, Málaga fell into the hands of Franco's troops with the help of some Italian motorized units. This capture tightened Franco's control over the Gibraltar area by his Navy. And, at the same time, it made the C-3 affair pass into the depths of oblivion. The Italians also stopped their submarine raids for a while after discussions with the French and the British. Instead, they opted for a more logical solution: by the end of February they sold two modern submarines to the Nationals. Those were the already mentioned Torricelli, and Archimede. Propaganda had it that they were C-3 and C-5 (C-5 had been lost for unknown reasons, having been seen for the last time in Bilbao on December 31st) that had deserted and changed sides, and they were painted with those markings. It could deceive no expert eye, but this way it was made clear that future attackers would not be "foreign". Later, the subs received their definitive names: General Sanjurjo and General Mola. Unlike their Republican counterparts, both were very active throughout the war. In August, the Italians resumed their attacks at an even higher intensity than before after Franco asked Mussolini for help in trying to interrupt the massive weapons shipments going to the Republicans from the USSR via the Mediterranean Sea. This time, even some destroyers took part in the action, and not only were the attackers foreign, but also some of the victims. That ended a month and a half later after tensions with Great Britain had escalated. The destroyer Havock was attacked in error, and her flotilla counterattacked with depth charges, damaging the Italian submarine. It became clear that there was more at stake than just Spanish affairs - the dispute over naval control of the Mediterranean had begun long before the Second World War started. At last however, tensions were eased and the naval powers came again to terms. That spring, the U-boats of the Saltzwedel flotilla returned to the Mediterranean, but this time as part of overt international surveillance operations. Nonetheless, one thing deserves attention. On June 3rd, Freiwald again took U-33, displacing Junker, until July 25th of that year. This is an exceptional event still needing an explanation, probably another secret mission of unknown nature. The last act of the C-3 story unfolded in 1998, when Antonio Checa, a lawyer interested in naval matters saw some bubbles of diesel fuel and oil coming up from the bottom some five miles away from the port of Málaga. After some research, he was sure that C-3 was there and he hired a submarine vehicle with which he took some video images although they were too blurred for definite identification. In 1998, the Spanish navy sent the Mar Rojo, a research and rescue ship to the area. With the help of side-scanning sonar and a team of divers, C-3 was positively identified. She lays at a depth of 67 meters, cut in two, a third on the forward end and two thirds aft covered by fishing nets, at position 36.40 N, 04.21 W. In the final balance of Operation Ursula, one may wonder whether it produced any benefits for the Kriegsmarine. At first sight, it seems that it didn't produce many. The results were poor and ironically the only successful attack took place when the operation had been called off. Torpedo performance was certainly disappointing. But there was also good news. First of all the boats themselves: the new Type VII that was to become the backbone of German submarine arm had been put to a tough test, and did fulfill the hopes placed in it. It proved to be a seaworthy and reliable submarine. And, if we think twice, the failures were not such bad news as they may seem. After all, they happened in a foreign war warning the Germans that there was hard work ahead to fix the problems. True, the problems were not completely sorted out when their own war broke out, but possibly the solution would have been delayed even more without that early warning. For the rest, it gave some very interesting experience, much needed in a reconstituted submarine arm that so far had a brief history and little experience, and even that limited to small coastal type U-boats. (1) Usually the terms used to name both sides in the Spanish Civil War reflect political attitudes. To avoid that, I will use the names with which each side referred to their own forces: Republicans by one side, Nationals by the other. (2) Until recently in Spain, as in Britain, there was a separate Ministry for naval affairs, the Ministerio de Marina. (3) She was sunk by a 203 mm. gun salvo at extreme range, 16 km, the second fired by the Canarias, which was observed by Royal Navy officers from Gibraltar. An eyewitness to this action who volunteered as a seaman to serve on the cruiser (after lying about his age), has told the author that word had spread around the Republican sailors of the installation in the cruiser of an almost miraculous aiming device by the Germans. In reality there was no time to install the ship's fire control system and the hit was a lucky shot. But it contributed to lowering the enemy sailors' morale, and may have played a part in the refusal of the returning Republican Fleet to engage the National cruisers when they sailed across the Straits. (4) Some sources mention that the team was under command of the ace of aces Lothar Arnauld de la Perrière. This is not true, but he did have another connection with this submarine. In 1931, when the Monarchy was replaced by the Republic in Spain, the thought of purchasing E-1 was abandoned and the Turks showed an interest in it. Either the Turks or the Germans engaged Arnauld de la Perrière to go to Spain and test the submarine. His favorable report prompted the Turkish navy to buy it. (5) There was another reason. The British Government demanded that all the warships were commanded by a Navy officer; if not, they would not be considered as warships. In fact, whereas the British Government was in favor of the Spanish Republic, though not very warmly indeed, the Royal Navy could hardly disguise its sympathy for Franco's Navy, which they considered a professional and brave Navy, in contrast with what they thought to be, not without grounds, a bunch of soviet-styled revolutionaries, incompetent and void of gallantry. (6) Tabacalera was the company that enjoyed the monopoly on the distribution and sale of tobacco. It had several small craft to combat tobacco smuggling. In the war they were used as coastal patrol boats.

Sonar scan of the wreck of C-3Footnotes

This article was published on 24 Mar 2005.