Soldier to the Last Minute

Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz and the Nuremberg Trial

3. Trial by Fire

In August 1945 in London a statute was created which formed the basis for a unique event in legal history, the international military tribunal at Nuremberg against war criminals 1945-1946.

Critics of this tribunal say that it was neither international nor military: Prosecutors and Judges were all members of the allied victors and although many of the defendants were tried because of their actions as soldiers, they were not allowed to wear uniform. Most of them bore after a long time in prison camps and wearing ill fitting civilian clothes a pitiful sight. While the idea of prosecuting war crimes was of course justified, the resulting procedure was ill constructed in various respects, the main criticism being that here laws were introduced that had previously not existed and were made legally binding even before their existence.

Several well renowned law experts all over the world criticized many of the verdicts spoken at Nuremberg. Another fact which left a shadow on the impartiality of the tribunal was that only German war criminals were tried at Nuremberg, although for the sake of fairness and justice all war crimes committed in the war, be it by German or allied soldiers, should have been investigated and brought to court. So a great chance was actually lost and many people referred to the Nuremberg trials as the tribunal of the victors, indicating a lack of fairness.

Whether this can be regarded as true, it is certainly so in the case of the trial against Großadmiral Dönitz. He was accused of conspiracy against peace, crimes against peace and crimes against martial law. He was not accused of crimes against humanity, as were the Nazi villains responsible for the incredible cruelty at the concentration camps. Although the Großadmiral did not care what happened to him as a person, he sensed what was the real cause for him being the defendant: to condemn the German U-boat warfare as an act of piracy and to justify his unlawful removal as head of state. Therefore, he asked the former Flottenrichter (Navy Judge in the rank of a Kapitän zur See) Otto Kranzbühler to be his lawyer. Kranzbühler shared the Großadmiral's concerns and did everything he could so that the German Navy and its U-boat arm would get out of the court unscathed.

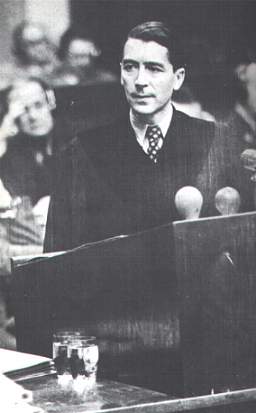

Also in pointing out by his personal appearance as Flottenrichter of the 'Kriegsmarine', he showed that if the head of the Navy is on trial, the Navy would care for his defence. When Kranzbühler appeared for the first time in the courthouse in the uniform of the Kriegsmarine with four golden cuff links indicating his rank as captain the russian guards presented their arms. Kranzbühler's outstanding detailed knowledge, his brilliant rhetoric and his logical presentation of evidence earned him the respect of even of his opponents. |

Flottenrichter Otto Kranzbühler |

Only by exceptional tactics could he achieve that the testimony of the Commander-in-Chief of the American Pacific Forces, Admiral of the Fleet Chester Nimitz, was admitted in court. Nimitz stated that from the very first moment of war, American submarines conducted an unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan. With that statement by one of their own military commanders, the Allied judges could not condemn Dönitz for unlawful warfare.

But a twist had to be found, to make it possible to pass a sentence not in favor of the Großadmiral. He was then condemned because he conducted (not planned, prepared or unleashed) an offensive war and his U-boats were well prepared and trained for war. This strikingly ridiculous reasoning has never since been applied. If it had been, every officer in the whole world training and preparing his men for battle (after all that is what the job of an officer is all about) should have been convicted. He was not found guilty of conspiracy, but guilty of crimes against martial law. The crime against martial law mainly consisting of not cancelling Hitler's order concerning the unlawful shooting of captured commando soldiers after Dönitz had become Commander-in-Chief of the Navy. That no commando soldier whatsoever had been caught and shot by Navy personnel according to this order did not bother the judges.

The reasoning of the verdict against Dönitz was very much debated by British and American law experts. Professor H.A. Smith, expert of international law at London University wrote in his book 'The Law and Custom of the Sea':

" The clumsiness and absurdity of this language perhaps indicate the embarrassment which the members of the Tribunal felt in dealing with the case of Dönitz, and it is not easy to ascertain from the rest of the judgment the precise facts upon which he was condemned."

Flottenrichter Kranzbühler remarked to the conviction of his client:

" This conviction was born out of the dilemma to take the Großadmiral into prison for political reasons. As I learned later on, the American law advisor made the proposal to the Allied control office to nullify the verdict."

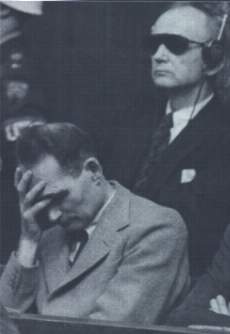

Karl Dönitz (behind Rudol Heß) during the pronouncement |

The reason why Dönitz was condemned was that the Allied victors could not allow the last head of

the German state to walk out of the courtroom as a free man. They had to condemn and lock him up

somewhere to justify their further political considerations about Germany.

So the Großadmiral was sentenced to ten years solitary confinement, even to early post war standards a rather harsh punishment. Flottenrichter Kranzbühler commented sarcastically on the sentence that this decision obviously reflected the minimum punishment to be expected from the tribunal in the case of proven innocence.

The verdict was regarded by many as an outrageous example of injustice and officers all over the world, amongst them some 120 Admirals of the U.S. Navy, considered the sentence as an unjustified attack on one of their brother officers. Dönitz received nearly 400 letters from Admirals, Generals, politicians, historians and journalists from all over the world, expressing their sympathy and regretting his fate.