The Discovery of U-86 (WWI)

by Jens Auer

In May 2006 Wessex Archaeology, an archaeological diving contractor in the UK, conducted Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) surveys on deepwater wrecks off the English South Coast.

The surveys were part of the “Wrecks on the Seabed” project, which is funded by the Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund (ALSF) and administered by English Heritage. The project aims to develop and improve methods for the archaeological survey of wreck sites.

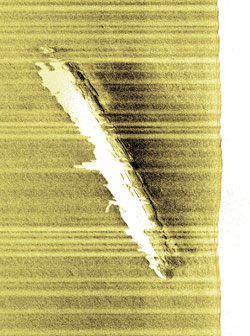

All wrecks chosen for the survey were listed as unknown at the start of the project. To prepare the ROV surveys, sidescan and multibeam sonar data was acquired for all study sites. This data gave an impression of the size of the wreck sites and helped to plan the survey.

Wrecksite 1003 was listed in the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) wreck database as an unknown vessel, possibly a sailing ship. Due to the depth on site the geophysical data lacked detail and the site was approached with an open mind.

It was a surprise for the survey team when a deck gun appeared on the camera monitor.

Although the visibility was very low, sometimes below 1m, it quickly became clear that site 1003 was the wreck of a previously unknown U-boat, possibly of WW1 origin. The Wessex Archaeology survey team then conducted a detailed ROV investigation of the wreck with the aim of identifying the u-boat.

A plan of the German Ms-type u-boat series U 63 - 65, which had been downloaded from Tony Lovell’s great webpage www.dreadnoughtproject.org and was used as a wallpaper on one of the survey computers, provided the first clues towards an identification.

Most of the features observed on the wreck could be identified immediately on the plan.

Further research after the survey allowed the identification of the u-boat as a U 81 type MS boat. Using uboat.net, most of the boats built of this type could be eliminated with U 86 left as the most likely candidate. Information in the National Archives confirmed that U 86 was scuttled in the English Channel, in a location very close to the survey position.

Once the identity of the “mystery” u-boat had been established the history and fate of U 86 could be reconstructed in more detail:

U 86 (Construction No 256) was ordered at the Germania shipyard in Kiel on the 23 June 1915. The keel was laid on 5 November 1915. The boat was launched on 7 November 1916. (Rößler 1997).

U 86 was commissioned on 30 November, 1916. Its first commander was Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Crüsemann, who was in charge of the boat until 22 June, 1917. On 23 June, 1917 Kapitänleutnant Alfred Götze took over as commander. Oberleutnant zur See Helmut Patzig was the last commander of U 86. He was appointed on 26 January, 1918 and served on the boat until it was surrendered at the end of the war on 11 November, 1918.

In 1917 and 1918 U 86 was assigned to the 4th U-Flotilla. Altogether the boat conducted 12 patrols (Helgason 2006) and sank a total of 33 ships (125,580 tons), warships excluded.

As an example for the general activity of U 86, information for the year 1918 has been extracted from the German naval war diary. During that year U 86 conducted operations in the Skagerrak, the Irish Sea, the North Sea and the Bristol Channel. The following ships were sunk:

- Kafue (6044grt), British steamer, on 1 May;

- Medora (5135grt), British steamer, on 3 May;

- Leeds City (4298grt), British steamer, on 7 May;

- San Andres (1656grt), Norwegian steamer on 12 May;

- Atlantian (9399grt), British steamer, on 26 June; and

- Covington (16,339grt), US troop transport, on 1 July.

(Admiralstab der Marine: Abteilung A, 1917-1918).

Llandovery Castle

In 1918 U 86 was involved in one of the worst war crimes committed by a u-boat commander during the First World War, the sinking of the British hospital ship Llandovery Castle and the subsequent murder of surviving crew members in the water.

Detailed information on the sinking of the Llandovery Castle and the subsequent trial of U 86’s officers in 1920 has been extracted from the book The Leipzig Trials (Mullins, 1921).

The Llandovery Castle, clearly marked as a hospital ship and known to the German government as such, was en route from England to Halifax with nurses, officers and men of the Canadian Medical Corps on board when she was torpedoed by U 86 in the evening of June 27 1918, about 116nm south-west of Fastnet. Of the 258 persons on board only 24 survived.

According to witness statements at the Leipzig war crime trial the commander of U 86, Oberleutnant zur See Helmut Patzig, gave the order to torpedo the Llandovery Castle even though he knew that she was a hospital ship, the sinking of which was illegal under international law and the Hague convention.

After the war Patzig fled the country and only the first and second officer of U 86, Dithmar and Boldt could be arrested and tried for their action in the incident.

Even though the Llandovery Castle sank within ten minutes, a number of boats were lowered successfully and the ship was abandoned in a calm and efficient manner. Three boats ultimately survived the sinking of the vessel undamaged and proceeded to rescue survivors from the water. They were interrupted by Patzig, who intercepted the boats and started interrogating crew members to obtain proof of the misuse of the hospital ship as an ammunition carrier. When no proof could be obtained, Patzig gave the command “Klarmachen zum Tauchen” and ordered the crew below deck.

Only himself, the two accused officers and the boatswain’s mate Meissner stayed on deck. However the U-boat did not dive, but started firing at and sinking the life boats to kill all witnesses and cover up what had happened. To conceal this event, Patzig extracted promises of secrecy from the crew, and faked the course of U 86 in the logbook so that nothing would connect U 86 with the sinking of the Llandovery Castle. As a result of the Leipzig trial, both Dithmar and Boldt were sentenced to four years of hard labour. Patzig, with whom the responsibility for the incident rested, was never found and prosecuted. Dithmar and Boldt were both released from prison after a few months due to the political changes in Germany.

U 86 was in the first group of U-boats that were handed over to the allies as part of the armistice treaty at the end of the war. She was taken from Brunsbüttel to Harwich on November 20, 1918 (Rößler 1997). From September 1919 to March 1920, U 86 was commissioned into the Royal Navy to test her design and make comparisons with other classes and later designs (McCartney 2003). After decommissioning, U 86 was dumped at sea at the end of June 1921. The damage at bow and stern of the U-boat suggests that in addition to flooding the tanks, charges were used to blow off the bow and stern sections.

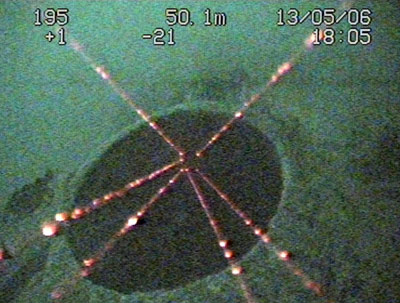

The following description of the wreck of U 86 is compiled using archaeological survey data as well as information from secondary sources. As the ROV was equipped with a laser measuring system, objects on the seabed could be measured to millimetric accuracy.

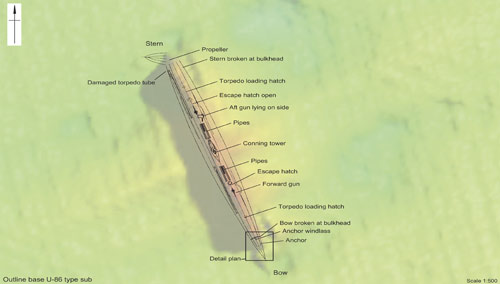

The vessel is lying on even keel with a slight list to port on the fairly flat seabed in NNW-SSE orientation with the bow in the SSE. Dimensions taken off the sidescan data suggest a length of 66m, a breadth of 6.5m and a height off the seabed of 3.5m for the wreck.

The outer hull of the vessel has largely disappeared, but the internal pressure hull is fairly intact. Bow and stern are heavily damaged and broken up from the bow bulkhead forward and the stern bulkhead aft. While the bow has collapsed and is lying partly buried in line with the vessel, the stern section has broken off and is lying at a 90 degree angle to the main hull, pointing westwards.

The wreck shows the twin hull construction typical of a U-boat: a pressure resistant inner hull and free flooding outer casing. Documentary sources indicate that the cylindrical pressure hull is built from riveted 12mm nickel-steel plates with external steel frames. According to the same sources the inside of the pressure hull is separated into compartments by a number of bulkheads made from 16-21mm thick steel. The forward and aft collision bulkheads are visible where bow and stern are damaged.

The pressure hull would have been enclosed within a steel outer casing which would have protected it. The rigid connection of outer casing and pressure hull enhances the strength of the pressure hull. On the wreck the outer casing is only partially preserved and the pressure hull is generally well-preserved and clearly visible in the upper deck area.

The conning tower is riveted onto the pressure hull and is fully preserved with only the protective casing and armour missing. Recesses for the navigation lights and maintenance access hatches were observed on both sides of the tower. The main conning tower hatch is situated aft of the periscope mountings and was found slightly ajar

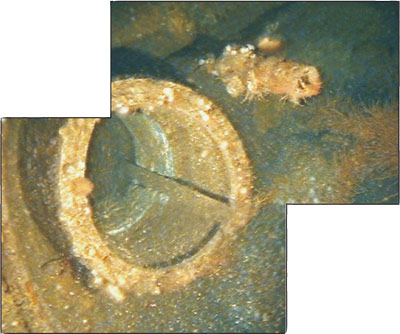

Two torpedo loading hatches were observed at bow and stern, aft and forward of the torpedo rooms. At the stern of the vessel, the engine room escape hatch is wide open. The forward escape hatch is sealed

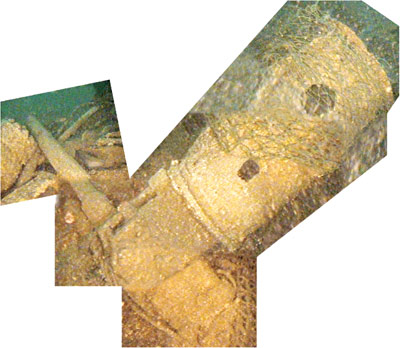

At the bow of the U-boat, the two bow torpedo tubes are split at the forward collision bulkhead. The scaling camera recorded an internal diameter of approx. 58cm for these tubes. The tube construction with outer reinforcement rings and bolted segments is clearly visible.

The two stern tubes are heavily damaged and lie at a 90 degree angle to the hull within the stern wreckage.

Most of the fittings that were originally located on the upper deck of the U-boat are preserved. The patent anchor is secured in the hawsehole in a recess on the side of the damaged bow section.

A number of compressed air cylinders were observed on top of the pressure hull along the length of the upper deck. These formed part of the U-boat’s compressed air system which was used to blow air into the dive- and ballast tanks. All cylinders were connected to a compressor in the control room and could be centrally recharged when the U-boat was on the surface. The width of individual air cylinders was measured as 46cm.

The U-boat was armed with two upper deck guns forward and aft of the conning tower. The forward gun is still attached to its mounting and trained upward. It is well preserved with a small amount of fishing gear snagged around the barrel. It appears that the calibre of the gun is larger than 10cm. The gun is fitted with a horizontally sliding breech block and top-mounted recoil cylinders. A comparison with all small calibre naval guns in use during WWI shows that it might be a German 10.5 cm/45 (4.1") Ubts L/45. This gun was in service from 1907.

The aft gun is also attached to its mounting but has fallen over to the port side. This gun appears to be the standard German U-boat gun of WWI, the 8.8 cm/30 (3.46") Ubts L/30. The gun is attached to a circular mounting rather than the collapsible mounting used on some U-boats. The 8.8cm L/30 Schnelladekanone was originally developed for river and coastal gunboats by Krupp in 1898. During WWI it became the standard U-boat armament.

On the conning tower, the mountings for three periscopes are visible. The two main periscope mountings are situated on top of the conning tower, forward of the escape hatch. Both periscopes were operated from the conning tower. The mountings seem to be empty and the periscopes could not be seen. The mounting for the emergency periscope is situated just forward of the conning tower. The emergency periscope was operated from the control room.

The column for the bridge steering wheel is situated forward of the two main periscopes. The main steering controls were located in the conning tower, but additional steering wheels were situated on the bridge, in the control room and aft in the torpedo room.

The U-boat’s ventilation system has collapsed onto the upper deck and is lying across the hull aft of the conning tower. At the stern the two propellers are still attached to the shafts. The port propeller is missing one of its blades.

More information on the Wrecks on the Seabed project and U 86 can be found online at: http://www.wessexarch.co.uk/projects/marine/alsf/wrecks_seabed/index.html

References:

- Admiralstab der Marine: Abteilung A, 1917-1918, Kriegstagebuch Band 2: U 86 der IV U-Flottille.

- Helgason, G., 2006, 'WW1 U-boats: U 86', http://uboat.net/wwi/boats/?boat=86.

- Mullins, C., 1921, The Leipzig Trials, London.

- Rössler, E., 1990, Die deutschen Uboote und ihre Werften: eine Bilddokumentation über den deutschen Ubootbau von 1935 bis heute, Bonn.

- Rössler, E., 1997, Die Unterseeboote der Kaiserlichen Marine, Bonn.

This article was published on 12 Mar 2007.