The Sinking of the S.S. Athenia

by Tonya Allen

The British steam passenger ship Athenia

The first incident of the U-boat war occurred just hours after the declaration of hostilities between Britain and Germany on September 3, 1939, when Oberleutnant Fritz-Julius Lemp, commanding U-30, attacked and sank what he took to be an armoured cruiser. His target was, in fact, the S.S. Athenia, a 13,500 ton passenger liner carrying 1,103 civilians, including more than 300 Americans hurrying home ahead of the clouds of war. This case of mistaken identity set in motion a large-scale cover-up on the part of the Reich, and had far-reaching consequences both for the subsequent conduct of the U-boat war, and for some of the key players in the affair - Lemp, Dönitz, and Raeder.

On the afternoon war was declared, OKM sent three radio messages, at intervals of about an hour, to all Kriegsmarine vessels indicating that a state of war was in force, that attacks on enemy shipping were to commence in accordance with the Prize Rules, and that vessels should feel free to begin hostilities without awaiting provocation. Lemp at that time was patrolling the area north-west of Ireland. Having absorbed these instructions, Lemp spotted a ship on the horizon, heading away from Britain in a north-westerly direction. He ordered U-30 to dive to periscope depth, took a look at the ship, and observed that the vessel was blacked out and zigzagging, and appeared to carry guns on her deck, all indications that she was an armed merchant or auxiliary cruiser, and therefore a legitimate target.

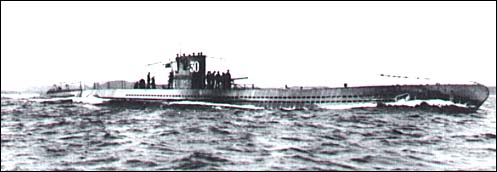

U-30 on the surface

According to the testimony of Dönitz at Nuremberg, Lemp had been specifically warned to be alert for armed merchant cruisers. Believing it was one of these which he had in his sights, but dispensing with the shot across the bow specified in the Prize Rules, he fired two torpedoes, one of which struck squarely, and one which misfired. U-30 dived to avoid the danger that the defective torpedo might circle back toward the U-boat. Surfacing once more and observing that the ship did not seem to be sinking, he fired a third torpedo, but this too missed. (Perhaps this third torpedo was responsible for the claims of survivors that U-30 shelled the Athenia after the initial torpedo strike.) Close enough now to note its silhouette, Lemp compared it with his Lloyd's Register and discovered his mistake. Soon afterwards, U-30 intercepted a plain-language transmission from the stricken ship identifying itself as the Athenia.

Although the Athenia's distress calls had eliminated the need to conceal his position, Lemp did not take the opportunity to make a report. Knowing full well the magnitude of his blunder, he opted to maintain radio silence, and did so until September 14. On this date, eleven days after the sinking of Athenia, he broke radio silence to report damage received in a confrontation with two destroyers following the sinking of British freighter Fanad Head, and to request permission to debark a wounded man in Iceland for medical attention. He still did not mention the Athenia.

He also did not aid the survivors, as the Prize Rules required, although he did do so after sinking S.S. Blairlogie some days later. Probably he had observed the Norwegian Knut Nelson in the area earlier in the evening, and felt that help would soon come to those in the lifeboats. Doubtless he believed that departing the scene before further attention was focused on U-30 was the wisest course.

The Knut Nelson was indeed soon on the scene. Two other merchant ships, City of Flint and Southern Cross, as well as three British destroyers, Electra, Escort, and Fame, aided in rescue operations.

Berlin learned of the sinking from British news broadcasts. The rude surprise of hearing of it in such a way was compounded by despair; the years of effort to erase the world's memory of the unrestricted submarine warfare of the first World War were cancelled out in an instant, in the first hours of the new conflict.

By comparing the location of the sinking with the U-boat deployment charts, it was clear that only one boat could have been responsible. Seeing the phantom of the Lusitania rising again, Hitler decreed that accusations would be confronted with categorical denial. To throw the British off the track still further, the Propaganda Ministry under Göbbels spread the story that the British had torpedoed the liner themselves in a scurrilous attempt to bring the United States into the war. This story was published in Volkischer Beobachter on October 23, fully a month after Lemp had confirmed the truth.

Lemp in the damaged U-30 limped slowly back from Iceland (having landed the wounded man there on Sept 19), arriving in Wilhelmshaven on September 27. He immediately reported to Dönitz that he had sunk the Athenia, and was sent to Berlin for a full debriefing.

The pretence that U-boats had had nothing to do with Athenia's demise was maintained for the duration of the war. The risk of admitting it was too great. Dönitz' own war diary recorded that the only successes of U-30's first mission were S.S. Blairlogie and S.S. Fanad Head. Lemp's own Kriegstagebuch was altered, although clumsily. The original carefully detailed pages were removed, and a false page inserted which did not match the rest of the diary as to handwriting. This new version of events placed U-30 200 miles west of her actual position on September 3.

There remained the matter of the wounded Adolf Schmidt, who had been left in Iceland. Lemp assured Dönitz that Schmidt would not be a security risk. In fact, before he had been taken off the boat, Lemp had made him swear an oath never to speak of the matter. Although he became a prisoner of the British when they occupied Iceland in 1940, and was interrogated repeatedly, he kept his silence. After the war, Schmidt provided testimony that was used at Nuremberg, believing that the oath was nullified by the termination of the war.

Consequences

In spite of initial fears in Berlin, the Athenia did not become another Lusitania; it was not as great a public relations disaster as it first had seemed. However, the very first U-boat success of the war did have far-reaching ramifications.

The next day, September 4, Hitler ordered that under no circumstances were attacks to be made on passenger ships, even in convoy, regardless of nation. This caused confusion as to what sort of vessel it was now permissible to attack. Freighters sometimes carried passengers; passenger ships sometimes carried troops. Were these legitimate targets?

Lemp was not court-martialled for his error, but neither was he promoted from the field as were many of his contemporaries. Thus he met his death in an incident that had far worse consequences for the U-Bootwaffe and the Reich than the sinking of the Athenia - the capture of U-110.

At the Nuremberg Trials, the cover-up and the accusations that the British had staged the sinking came back to haunt Raeder, who was accused of committing deliberate fraud in the Athenia affair.

Of the Athenia's passengers and crew, 112 were killed (93 of them passengers) in the initial explosion or died later as a result of the sinking.

This article was published on 21 Mar 1999.

Buy this title at amazon.co.uk |

Books dealing with this subject include

|